Private William James Acheson

William James Acheson (or Atcheson) was born on 14 August 1896 at Glencunny, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, the only child of herd Hugh Acheson and his wife Elizabeth (nee Rankin). By the time of the 1911 Census he was living at Glencunny with his parents, his father working as an agricultural labourer.

Acheson enlisted in the North Irish Horse at Enniskillen in January-February or April 1913 (regimental number 792, 793, 839 or 840 – later Corps of Hussars No.71105 or 71126). He embarked for France with A Squadron on 17 August 1914, seeing action on the retreat from Mons and advance to the Aisne. (It is odd that Acheson's name does not appear on the 1914 Star medal rolls.)

Acheson remained with A Squadron until the end of 1916, when he was injured by a kick from a horse, making him unfit for any further front-line service. He spent the remainder of the war at the North Irish Horse reserve depot at Antrim.

On 8 August 1919 Acheson, by then a farmer at Crownhall, County Fermanagh, married Margaret Kathleen Devlin at Rossorry Church of Ireland Parish Church.

Acheson's experiences in the war are told Niall McGinley's book Donegal, Ireland and the First World War (below).

Though a Fermanagh man Willie Acheson was born quite near the Donegal border: at Crownhall, Enniskillen, in August 1896. His memories of World War One are still clear (1986); his physical health is also good and he is kept active by his friendly Irish setter dog and an odd run on the bicycle. He is a frank, friendly man, willing to talk about [his] experiences ...

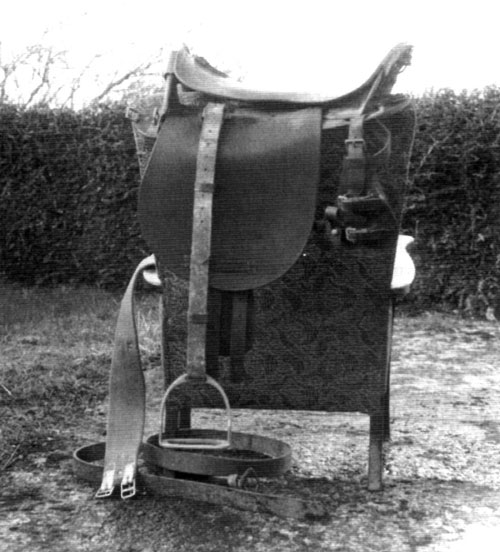

Being a farmer's son and a Protestant, it was natural that he would join the North Irish Horse. In 1913 Sergeant-Major Barnes signed him on in Enniskillen; although eighteen was the lower age-limit Barnes would write down the age you told him – provided you had the height. The contract was for four years: you brought your own horse, or one you had hired, to camp where a month's training was done; it was expected that throughout the rest of the year about one day per month would be set aside for group exercises. Pay was about £5 (self + horse) and the army insured the horse.

A fortnight before going to camp they got saddle and bridle so that both could be polished to perfection in time; the same period was allowed afterwards for repolishing. Camps were held at Finner, and Annalong Co. Down. After reveille every morning long slacks were donned and an hour was spent grooming the horse. A person who never groomed a horse might wonder how an hour could be spent at the job; but as an officer inspected the job afterwards – rubbing the hair the wrong way for instance, in search of dandruff every minute of that hour was needed. As well as brush and curry-comb the men had towels, to wash out the sleep from the horses’ eyes! Your name and number were taken if your grooming was considered unsatisfactory.

Only then was breakfast eaten; the food was ample and of good quality. Afterwards a half-hour was allowed for shaving and getting into riding uniform; off to the parade-ground then, or beach, for cavalry drill. Their riding instructor was Dunlop of the Scotch Greys, a man who wouldn't be patient with a rider clambering into the saddle like a rock-climber. Standing with back to the horse's neck you caught the mane with left hand, reached across for the saddle, and up you got. Eventually it was learned to do this in drill-time; you then practised riding in formation, turning right or left, dismounting, saddling, etc. – all in drill-time. The horse got to know you of course, so that he more or less anticipated your commands: when the officer was singing out "LE-EFT turn" the horse would have swung left before he had finished the first word. If the horse was given the odd delicacy like a lump of sugar it would follow its rider around the yard when free.

Willie had just got back from the 1914 camp and still had his harness at home when war-alert was announced. All went to the barracks at Enniskillen where the Bedford regiment was stationed. Apart from an odd parade and routine duties they hadn't much to do; after five o'clock tea he could cycle home and be in the barracks again by 10 p.m.

After about ten days of this Lord Enniskillen addressed them: "Good news men. I have been in communication with the War Office and we’ve been ordered to entrain tomorrow at 7 a.m. for France. All ranks are confined to barracks." The following day they travelled to Dublin where they embarked for the war zone.

Willie wasn't impressed by the British Army's treatment of its soldiers. The uniform was a khaki make-shift that you wouldn't give to a dog; the steamer which brought them to France was just a commandeered coal-boat; the horses were better cared for than the men: the notice on each railway-wagon stated the maximum capacity: 40 men, but only 8 horses!

In France an advance party would commandeer a field (for which the owner was paid) and two pegs would be driven into the ground about twenty yards apart, for every ten horses; these pegs were joined by a rope to which the animals were tethered. As hay was bulky to transport and to store, corn and bran were the usual fodder. A sergeant was put in charge of each group of horses: if they were tired there was no bother, but they'd pull out the pegs if cold or uneasy.

The men might have to sleep out, using great-coat, horse blanket and own blanket for warmth. If possible they'd be billeted on a house, say four per building; you might get a double bed or sleep on the floor. Other times their shelter might be the ruins of a house or barn.

Willie found the French civilians difficult and greedy. Here and there were taps for watering the horses but some areas had none; if a Frenchman saw you taking water from his pump it was: ‘No touch’. Once, on such an occasion, Willie had his bucket half-full: he emptied it on the cranky farmer and trotted off before his number could be taken. Another time he and two others were in a pub; a Scot called for 'vin blanc' and they all downed their drink. Willie then ordered another drink at the counter, paid in English money and brought the glasses back to his pals; they asked him what change he'd got and when they counted it discovered he'd been short changed. Willie, a big strong farmer of eighteen then, asked the owner for the correct change; "Non, Non", was his only reply. Willie grabbed a piece of the counter, wrenched it from its hinges and brought it down on the man's head. Luckily for him it caught on a shelf on the way down so his head did not get the full force of the blow; a lot of bottles and glasses were broken. A military policeman came to the scene who took the culprit to Emerson Herdman (Sion Mills):

"Acheson, how did you get into such a row?" said he smiling. "Tell me exactly what happened."

When the whole story had been told Herdman could only laugh. "We'll have to give you four days."

"What will I get him to do?" asked the sergeant-major.

"Oh", said Herdman, "whatever you like. He can sweep the lanes or any place else."

The men found Belgians more to their liking: less greedy and not trying to take advantage of the men at every turn.

The first big charge they took part in was at Kemmel Hill using swords. They became hemmed in by Germans. A comrade, Dan Wallace, never called Lord Enniskillen (John Cole) anything but John. "You may blow the whistle, John, 'cause we’re cornered here." Blow it he had to, and all retreated. Willie met a relation of Dan's later who, referring to Lord Enniskillen, said: "If he stood Dan he could stand anything."

The North Irish Horse were with the 4th Division and had to take their turn in protecting the infantry as they retreated from Mons south to the Marne. Fighting was done in groups of four: number three in each group was the holder. He stayed mounted to hold the reins of the other three while they fought on foot with sword or rifle; a person might be number three twenty times in succession, or never. During this retreat Willie got spattered with shrapnel but no serious damage was done. Like most of the rank-and-file he had no confidence in officers like commander-in-chief French. Frequently such men had shown no promise in other walks of life so their wealthy parents would buy them a commission in the army, hoping they'd be able at least to 'hold down' such a job. If these men kept their bibs clean they would usually rise gradually as vacancies occurred – whether they were capable or not – and thus end up, perhaps, commanding thousands of professional soldiers most of whom knew far more about war and strategy than their commanders.

There were, of course, farriers to shoe the horses; a neighbour, Daly, was farrier-sergeant with the N.I.H. shoes however were frequently pulled loose so the rider would hammer home one himself if he heard it clattering on the road. While attending to his horse near the Marne in January 1916 Willie got a kick in the knee from a Belgian horse; that was the end of this war for him.

Back in Ireland, after hospitalisation, he worked in the North Irish Horse centre near Antrim town. In August 1919 he married – his wife died only recently. Seeing an advertisement in a newspaper one day seeking drivers for Crossley-tenders he said to her:-

"There's a job would suit me."

"Did you not get fighting enough?" said she. "I'd live under a bush first!"

Willie applied and got the job, first driving a Crossley and then an armoured Lancia; the latter was freezing in winter and roasting in summer. Eventually he got a job in the Belfast shipyards where he spent the rest of his working life.

Transcript above and images from Niall McGinley, Donegal, Ireland and the First World War, pp.233-39